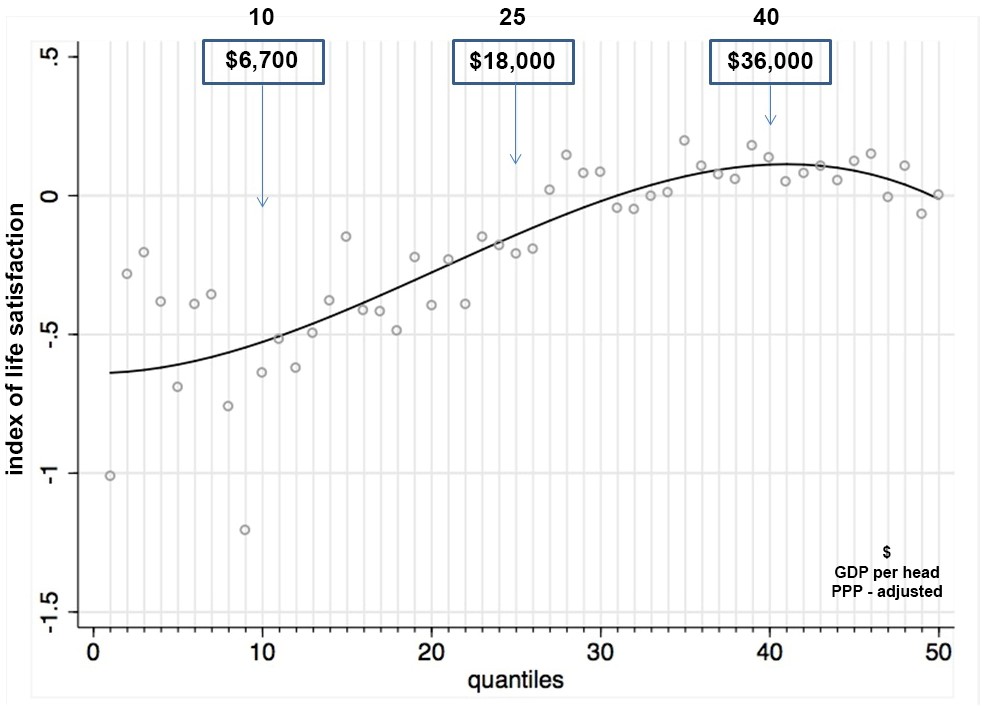

As countries get wealthier, their average life satisfaction rises. But it peaks and then declines after the $33,000 GDP/capita “bliss point.” (Eugenio Proto and Aldo Rustichini)

Zdroj: The Washington Post

A new study by economists Eugenio Proto and Aldo Rustichini finds that life satisfaction tends to be higher in countries with higher average incomes. In economist-speak, that means that life satisfaction correlates with GDP per capita, adjusted for purchasing power parity. What may come as more of a surprise is their finding that average life satisfaction actually peaks with countries that have an average annual income of about $33,000; after that, life satisfaction tends to drop as wealth rises.

The chart at the top of the page shows the authors’ top-level findings. The x-axis is GDP per capita, another way of saying average national income; the y-axis is life satisfaction, which is sort of another way of saying happiness (more on this later). As you can see, life satisfaction goes up along with wealth, then it peaks and starts declining. Proto and Rustichini are the not the first economists to study the relationship between national wealth and happiness (more on this later as well), but one way they’ve done things differently is to divide the country data into 50 subsets or “quantiles” and then look at the relationship between wealth and life satisfaction within those quantiles.

They also looked at the data just for European economies within the European Union. (They didn’t include countries that joined the E.U. after 2004, to avoid “confounding factors.”) The results seemed to bear out the same conclusion: that more wealth means more life satisfaction — up to a point. Here are the European data; the most interesting chart is the one on the right, that excludes outliers:

Data just from Europe shows a similar relationship between national wealth and life satisfaction. (Eugenio Proto and Aldo Rustichini)

To be clear, life satisfaction does not decline by an awful lot for richer countries. The strongest effect of national incomes on life satisfaction is seen in the poorest countries, where a little bit more money seems to go a relatively long way in correlating with more life satisfaction. The authors conclude by asking, “Our econometric analysis implies that long-term GDP growth is certainly desirable among poorer countries, but is it a desirable feature among developed countries as well?”

The big caveat here is that this is not the only study on the relationship between wealth and happiness, and other studies have reached very different conclusions. A famous 1974 study by the economist Richard Easterlin found that a country’s average happiness bore basically no relationship to its national wealth, as long as that country had enough money that people’s basic needs were met (he did find, though, that people within a specific country were likelier to be happier the richer they got). Proto and Rustichini, in their study, do talk about the so-called Easterlin Paradox and say that they see it holding broadly true across rich countries.

Other studies, such as this one conducted by economists Betsey Stevenson and Justin Wolfers, found something very different: that happiness goes up with national income and doesn’t peak, although they arrived at this conclusion in part by evaluating “life satisfaction” as distinct from happiness. The questions of whether life satisfaction and happiness are the same thing, and why those two metrics might show such different results, is another kettle of fish. But the theory here, as my colleague Dylan Matthews put it, is that “happiness rises constantly with income.” No “bliss point.”

So the question of how wealth relates to happiness is by no means settled. But one point on which all but Easterlin seem to agree is that people in poorer countries benefit most, in terms of “life satisfaction,” by a boost to national incomes. That’s pretty significant.

Max Fisher is the Post’s foreign affairs blogger. He has a master’s degree in security studies from Johns Hopkins University.